Contents

Introduction to Skin Structure

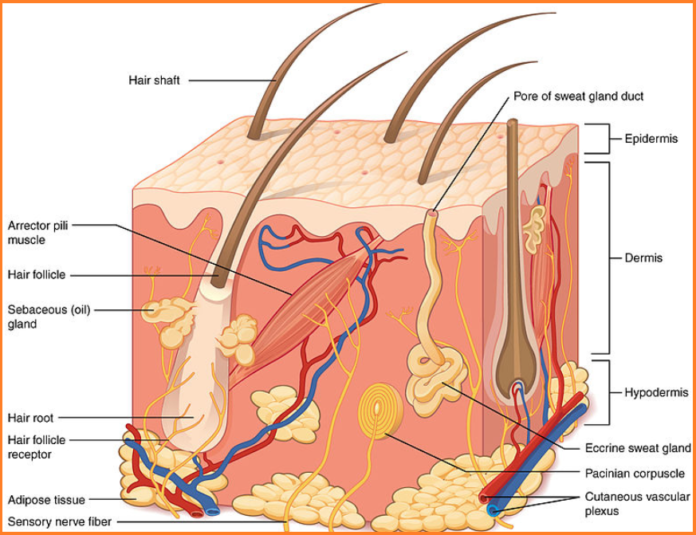

The skin, recognized as the largest organ of the human body, is an intricate and multifaceted system comprising three primary layers: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. Each of these layers serves distinct and essential functions, collectively contributing to the skin’s role as a protective barrier and a regulatory entity for the body. Understanding these layers is fundamental to appreciating how the skin operates to safeguard and maintain overall health.

The outermost layer, the epidermis, acts as the body’s first line of defense against environmental hazards such as pathogens, ultraviolet radiation, and physical abrasions. It is composed of tightly packed cells that undergo continuous regeneration, ensuring the skin remains resilient and capable of repairing itself. Within the epidermis, melanocytes produce melanin, the pigment responsible for giving skin its color and protecting against UV damage.

Beneath the epidermis lies the dermis, a robust layer rich in collagen and elastin fibers, which provide structural support and elasticity. This layer houses vital components such as blood vessels, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles. The dermis plays a crucial role in thermoregulation through the sweat glands and in maintaining skin hydration with sebum secretion from the sebaceous glands. Additionally, the sensory receptors within the dermis enable the perception of touch, pain, and temperature.

The deepest layer, the hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous layer, consists primarily of fat and connective tissue. This layer acts as an insulator, conserving body heat, and serves as a cushion to protect internal organs from mechanical injuries. The hypodermis also stores energy in the form of fat, which can be metabolized when the body requires additional fuel.

By delving into the structure and function of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, we gain a comprehensive understanding of how each layer contributes to the skin’s overall efficacy as a barrier and a regulatory organ. This foundational knowledge is essential for further exploration into the complexities of skin health and disease.

The Epidermis: The Body’s First Line of Defense

The epidermis is the outermost and thinnest layer of human skin, serving as the primary barrier between the body and the external environment. This vital layer is composed of several sublayers, or strata, each playing a crucial role in protecting the body from various environmental hazards such as pathogens, chemicals, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

The epidermis is predominantly made up of keratinocytes, which are cells that produce keratin, a protective protein. The process of keratinization is essential for maintaining the integrity of the skin. Keratinocytes are continuously generated in the deepest sublayer of the epidermis, known as the stratum basale. As these cells mature, they migrate upwards through the other strata, eventually reaching the outermost layer called the stratum corneum. Here, they form a tough, protective barrier before being shed off in a cycle that typically lasts about 28 days.

Apart from keratinocytes, the epidermis also contains melanocytes, which are specialized cells responsible for producing melanin. Melanin is the pigment that gives skin its color and offers some level of protection against UV radiation. The amount of melanin produced by melanocytes varies among individuals and is influenced by genetic factors and exposure to sunlight. Increased melanin production occurs as a natural response to UV exposure, resulting in tanning, which helps to shield deeper layers of skin from potential damage.

Additionally, the epidermis houses Langerhans cells, which play a pivotal role in the immune response by detecting foreign substances and initiating an immune reaction. This multifaceted layer is not just a physical barrier but also an active participant in protecting the body from infections and other external threats.

In summary, the epidermis is a dynamic and complex layer that serves as the first line of defense for the human body. Through the continuous process of keratinization and the production of melanin, the epidermis ensures the skin remains resilient and capable of withstanding various environmental challenges.

The Dermis: The Functional Core of the Skin

The dermis, situated just beneath the epidermis, represents the functional core of the skin. Noteworthy for its thickness compared to the epidermis, the dermis plays a pivotal role in maintaining skin health and functionality. This layer is primarily composed of collagen and elastin fibers, which are indispensable for providing the skin with strength and elasticity. These fibers ensure that the skin remains resilient and capable of withstanding various physical stresses.

One of the most critical functions of the dermis is its extensive network of blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. The blood vessels within this layer facilitate the regulation of body temperature by either dilating or constricting, depending on the body’s needs. Concurrently, these vessels play a vital role in nourishing the skin cells and removing metabolic waste, thus maintaining overall skin health.

The dermis is also integral to sensory perception. It houses a multitude of nerve endings that enable the skin to detect and respond to various stimuli, such as touch, pain, and temperature changes. This sensory capability is essential for protecting the body from potential harm by providing immediate feedback from the environment.

Moreover, the dermis is crucial in wound healing. When the skin sustains an injury, the dermis activates a complex healing process that involves the formation of new tissue and blood vessels. This regenerative capability underscores the importance of the dermis in maintaining the skin’s integrity and function over time.

Additionally, the dermis contains sebaceous and sweat glands, which are essential for skin health. Sebaceous glands secrete sebum, an oily substance that lubricates and waterproofs the skin, while sweat glands aid in thermoregulation and excretion of waste products. Together, these glands contribute significantly to the skin’s protective barrier and its ability to maintain homeostasis.

In summary, the dermis is a multifaceted layer that not only provides structural support but also plays a crucial role in sensory perception, thermoregulation, wound healing, and overall skin health.

The Hypodermis: The Skin’s Insulating Layer

The hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous layer, represents the deepest layer of human skin. This essential component is primarily composed of adipose (fat) tissue and connective tissue, which confer a multitude of critical functions. One of the most significant roles of the hypodermis is its ability to provide insulation, thereby maintaining the body’s core temperature. By storing fat, the hypodermis acts as a thermal insulator, ensuring that the body retains heat in cold conditions and dissipates heat in warmer environments.

Additionally, the hypodermis serves as a vital shock absorber, protecting underlying tissues and organs from mechanical injuries. The presence of fatty deposits within this layer cushions the impact from external forces, reducing the risk of damage to deeper structures such as muscles and bones. This protective mechanism is particularly crucial in safeguarding the body during physical activities and accidental trauma.

The hypodermis also functions as an energy reservoir, storing fat that can be metabolized to meet the body’s energy demands. This stored energy is essential for various physiological processes, especially during periods of fasting or intense physical exertion. Moreover, the fatty tissue in the hypodermis plays a role in hormone production, particularly hormones related to fat metabolism and appetite regulation.

In terms of structural connectivity, the hypodermis anchors the skin to the underlying muscles and bones, facilitating the skin’s mobility and flexibility. This anchoring mechanism ensures that the skin remains stable while allowing for a range of movements without detachment or injury.

Overall, the hypodermis is indispensable for maintaining overall skin health. Its multifaceted functions not only contribute to thermal regulation and protection but also support metabolic and hormonal processes that are vital for the body’s homeostasis. Understanding the role of the hypodermis underscores its importance in both dermatological health and general well-being.