Contents

Anatomy of the Carpal Tunnel

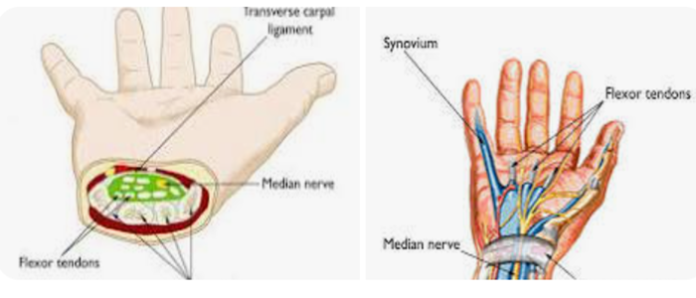

The carpal tunnel is a narrow, rigid passageway located on the palmar side of the wrist. It is formed by the carpal bones, which create a concave surface, and the flexor retinaculum, a strong band of connective tissue that spans across the top. This complex structure serves as a protective channel for various important anatomical components, ensuring their proper function and protection.

The boundaries of the carpal tunnel are defined by the carpal bones on the dorsal side and the flexor retinaculum on the palmar side. The bones include the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform on the proximal row, and the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate on the distal row. These bones create a tunnel-like structure that houses several critical elements.

Within this confined space, the carpal tunnel accommodates nine flexor tendons and the median nerve. The flexor tendons include the four tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis, the four tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus, and the single tendon of the flexor pollicis longus. These tendons are essential for the flexion movements of the fingers and thumb, enabling a wide range of hand functions from gripping to fine motor tasks.

The median nerve, another crucial component passing through the carpal tunnel, is responsible for both motor and sensory functions. It provides motor innervation to the thenar muscles, which are involved in the movement of the thumb, and sensory innervation to the palmar side of the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and the radial half of the ring finger. This nerve plays a pivotal role in the dexterity and sensation of the hand.

The integrity and functionality of the carpal tunnel are vital for hand movement and sensation. Any compromise to this structure, such as swelling or compression, can lead to conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome, which significantly affect hand performance and quality of life.

Functions of the Carpal Tunnel

The carpal tunnel is integral to the seamless connection between the forearm and the middle compartment of the palm. This narrow, rigid passageway, located on the palm side of the wrist, serves as a conduit for the median nerve and several tendons that enable the movement of the fingers and thumb. Proper functioning of the carpal tunnel is crucial for maintaining dexterity and the fine motor skills required for various hand movements.

At the core of the carpal tunnel’s functionality is the median nerve, a critical component that transmits both sensory and motor signals to and from the hand. This nerve is responsible for providing sensation to the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and part of the ring finger. Additionally, it controls the motor functions of several small muscles in the hand, known as the thenar muscles, which allow for the thumb’s opposition, flexion, and abduction movements. The median nerve’s role in conveying these signals ensures that the hand can perform precise and coordinated activities.

Furthermore, the tendons that pass through the carpal tunnel facilitate the bending and flexing of the fingers. These tendons are part of the flexor muscles located in the forearm, and their smooth gliding within the tunnel is essential for efficient hand movements. When these tendons move, they pull on the fingers, enabling actions such as gripping, pinching, and manipulating objects. Any impairment in the carpal tunnel can disrupt these functions, leading to reduced hand strength and dexterity.

In essence, the carpal tunnel’s role is to protect and support the median nerve and flexor tendons, ensuring the hand’s functional capabilities. By safeguarding these vital structures, the carpal tunnel maintains the intricate balance between sensory perception and motor control, which is indispensable for performing everyday tasks with accuracy and ease.

Common Conditions Affecting the Carpal Tunnel

The carpal tunnel serves as a critical passageway in the wrist, housing the median nerve and several tendons. Various medical conditions can compromise this anatomical structure, with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) being the most prevalent. CTS arises when the median nerve is compressed, often due to repetitive hand movements, wrist anatomy, or underlying health conditions.

Repetitive hand movements, such as typing or using vibrating tools, are common causes of CTS. Continuous strain on the wrist can lead to inflammation and swelling within the carpal tunnel, placing undue pressure on the median nerve. Wrist anatomy also plays a significant role; individuals with a smaller carpal tunnel are more susceptible to developing CTS. Additionally, health conditions like diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and thyroid disorders can exacerbate the risk by causing fluid retention or inflammation.

The hallmark symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome include pain, numbness, and tingling in the hand and fingers, particularly the thumb, index, and middle fingers. These symptoms often worsen at night, potentially disrupting sleep. Some individuals may experience weakness in the hand, making it difficult to grasp or hold objects. Early diagnosis is crucial to managing CTS effectively. Diagnostic methods typically involve a physical examination and patient history, alongside specialized tests such as nerve conduction studies and electromyography, which assess the function of the median nerve.

Other conditions that may affect the carpal tunnel include tendinitis, which involves inflammation of the tendons passing through the tunnel, and ganglion cysts, which are noncancerous lumps that can develop along the tendons or joints. Both conditions can contribute to the compression of the median nerve, mimicking symptoms similar to CTS. Accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to relieving symptoms and preventing further complications.

Treatment and Prevention of Carpal Tunnel Issues

Addressing carpal tunnel syndrome involves a combination of treatment options and preventive measures aimed at alleviating symptoms and avoiding recurrence. Non-surgical treatments are often the first line of defense. Wrist splinting, for example, is a common approach that involves wearing a brace to keep the wrist in a neutral position, especially during sleep. This helps to reduce pressure on the median nerve, thereby alleviating pain and numbness.

Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, can also be effective in reducing swelling and relieving pain associated with carpal tunnel syndrome. Physical therapy is another vital component of non-surgical treatment. A physical therapist can guide patients through exercises designed to enhance flexibility, strength, and overall function of the wrist and hand muscles.

In cases where non-surgical treatments prove insufficient, surgical options may be considered. Carpal tunnel release is a common surgical procedure aimed at relieving pressure on the median nerve. During this procedure, a surgeon cuts the transverse carpal ligament to enlarge the carpal tunnel and decrease nerve compression. This surgery can be performed using either an open or endoscopic technique, both of which aim to provide long-term relief from carpal tunnel symptoms.

Preventive measures are crucial in managing and mitigating the risk of developing carpal tunnel syndrome. Ergonomic adjustments in the workplace or home environment can significantly reduce strain on the wrists. This includes using keyboards and mice designed to minimize wrist extension, maintaining a neutral wrist position, and ensuring that workstations are set up to support proper posture.

Additionally, taking regular breaks from repetitive activities can help prevent the onset of symptoms. Incorporating exercises that strengthen the wrist and hand muscles can also be beneficial. Stretching exercises, such as wrist flexor and extensor stretches, along with strengthening routines focusing on grip and finger dexterity, can contribute to overall wrist health.